-

Services

-

“Laine IP is driven by a passion for trademark law and brands. It positions itself as a trusted partner to the businesses it assists and has astutely developed its offering to include services lines that fuel company growth and strengthen existing frameworks. Anchoring the practice, Tom-Erik Hagelberg stands out for his energy, enthusiasm and no-nonsense approach. Although equally adroit on both sides of the contentious/non-contentious divide, Hagelberg is best known for his finely honed strategies and opposition capabilities.”

Tom-Erik Hagelberg

WTR1000 is the only independent definitive guide dedicated to identifying the world’s leading trademark professionals and firms in over 80 jurisdictions around the globe. All the WTR1000 rankings for Finland can be found here.

Press release for the WTR 1000 can be found here.

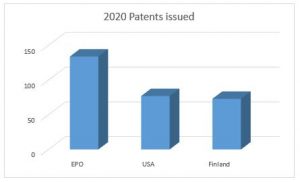

We are pleased to announce that our firm was the representative of record for our clients on: 134 granted European (EPO) patents; 77 issued US patents; and 73 granted Finnish patents in 2020.

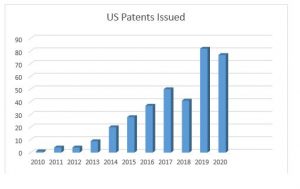

The 77 issued US patents brought the overall total number of US issued patents to over 350 for Laine IP Oy’s internal US Team since its creation in 2010.

We wish our clients continued success in 2021!

In November we published a brief article about EPO’s new practices relating to oral proceedings. Some changes came into effect with the new year, namely with respect to Boards of Appeal and hearing of witnesses.

Previously, a Board of Appeal could only hold oral proceedings by ViCo if all the parties agreed. As of 1.1.2021, the decision is at the Board’s hands, and no consent is needed from the parties.

Additionally, the EPO changed its practice (as well as rules 117 and 118 of the European Patent Convention) as of 1.1.2021 to allow hearing of a witness also by ViCo. For any oral proceedings held by ViCo, the witness must also be heard by ViCo and in the presently unlikely event of the oral proceedings being held at the premises of the EPO, the witness can still be heard by ViCo. Hearing of witnesses is not that common during EPO prosecutions, most cases concern oppositions where a public prior use has been presented against novelty. In such a case, a witness may be required to be heard to prove such use.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

We thank you all for the past year and

look forward to a successful 2021.

Laine IP Oy

* * *

This year we have made a donation to the Finnish Medical Foundation.

This could-would determination is, however, possible to utilize also as part of the problem-solution approach.

The could-would method is based on determining whether a person skilled in the art would have made a specific improvement to prior solutions, based on the available prior art. In other words, it is not sufficient that he/she could have made said improvement.

In the problem-solution approach, this could-would approach can be utilized when discussing the publication selected to represent the closest prior art. In said context, it is not sufficient to indicate that the person skilled in the art could have carried out the required changes to the closest prior art, to modify its teachings to provide the invention being evaluated. Instead, the prior art should guide the skilled person in the required direction, so that he/she would have made the required modifications.

Therefore, it is often determined, in this context, whether any of the known publications, i.e. the prior art, includes an incentive, based on which the person skilled in the art could have decided that the required direction of modifications would have been worth testing.

An example would be a case where a certain feature, missing from the publication representing the closest prior art, would make it possible to achieve a certain improvement for a certain product. If it is mentioned in the same publication that it would be of benefit to achieve said improvement, the publication could be considered to include said incentive, which would guide the person skilled in the art towards finding said improvement from another publication.

Similarly, the prior art can be examined to determine whether it includes a teaching that guides the person skilled in the art in the wrong direction (i.e. a “teaching against” the required modification).

For example, if a certain feature is included only in a comparative example, and is interpreted to have a negative effect on the invention described in this document, it can be considered unlikely that the person skilled in the art would still use that feature from another document and combine it with the disclosure from the closest prior art.

As in other methods related to the evaluation of inventive step, only the factors that were commonly known already before the filing date of the patent or patent application to be evaluated can be taken into account in the could-would determination.

See also:

The problem-solution approach in determining inventive step

Difficulties in the determination of the objective technical problem

The objective technical problem is the problem that is solved by the invention to be evaluated, but not solved by the publication considered to represent the closest prior art.

For example, the objective technical problem can be defined as how to improve the solution described by the closest prior art, or it can be defined as how to achieve a certain desired effect in an alternative manner.

In defining the objective technical problem, the point of comparison should be only the publication that has been selected to represent the closest prior art. At this point no other prior art should be considered, no matter how well known. This alone has already proven to be challenging.

Also other difficulties can be encountered when defining the objective technical problem. The definition should refer to some improvements or advantages achieved using the invention to be evaluated, and although this improvement or advantage is not required to be explicitly mentioned in the patent application, it should still somehow be apparent based on the application that such an effect is achieved.

For example, if arguments in favor of inventive step refer to the effect of a particular chemical agent in a particular context, it is sufficient if it is commonly known that said agent has said effect in said context.

Such required effects are, however, not always commonly known.

Although the advantages achieved using the invention are regularly referred to in patent applications, these do not necessarily include the specific advantages that are used in defining the objective technical problem. One possible reason for this is that the advantages used to define the objective technical problem should be ones that are achieved specifically in view of the closest prior art. The closest prior art might, however, not have been known by the applicant when drafting the patent application.

In defining the objective technical problem, any features of the invention, which fail to provide a technical effect (non-technical features), should be disregarded. Such features include, among others, features relating to:

It is, however, not always a simple task to determine which features are non-technical. In practice, most features of inventions have some impact on the overall technical effect of the invention, even if they, as such, are non-technical.

See also:

The problem-solution approach in determining inventive step

Optitune has developed an ultra-flexible hard coating material with best-in-class optics and durability based on its proprietary siloxane-based technology. Recently, more and more top brands are introducing foldable phones based on large foldable OLED displays. Such displays employ thin flexible substrates which require coatings to protect against fingerprints, scratches and reflections. Revenues of these free-form displays are expected to reach US$ 8.9 billion by 2025, which is 13 times the revenue generated by this segment today.

Merck, an established leader in display materials will use their brand and customer network to bring Optitune’s product to the market. Merck has played an integral role in the development of display technologies for more than 50 years in the commercialization of LCD and now OLED materials.

“Merck, with their long-standing reputation in display materials and global reach is the ideal partner for Optitune and is a testament to the quality of the materials we’re producing here in Oulu,” comments Optitune CEO Ari Kärkkäinen.

Optitune has developed a range of siloxane-based coating products which are designed to improve the optical performance of displays while lowering power consumption. The extremely robust coatings render surfaces easy-to-clean and difficult to scratch. Optitune’s coatings portfolio covers applications ranging from electronic displays and touch panels to common kitchen appliances.

This imaginary person has the average skill of the specified technical field, and knows what has been published in that field, as well as what belongs to the common general knowledge of that field. His/her line of work is always selected based on the invention to be evaluated, and he/she is capable of such routine research that is common in the relevant field.

The person of average skill in the art participates in the continuous development of his/her technical field, and is even capable of making simple suggestions for solving problems, but only if clearly guided in the right direction. He/she does, however, not make conclusions based on his/her knowledge.

The level of knowledge of the person of average skill in the art is not clearly defined, but can vary from one field to another. It is affected, among others, by how much the knowledge of that field is developed, how significant problems to be solved exist in said field, and what educational levels the inventors in that field typically have.

Inventive step, for example, is examined with the help of the person skilled in the art, by determining whether a new solution is obvious based on the knowledge of the person of average skill in the art. Briefly, if the person skilled in the art compares the invention to a disclosure in a close field, and finds the difference between these solutions to be such that he/she would try it out in his/her routine work, the solution of the invention is obvious, and therefore not inventive.

The person skilled in the art is also consulted when determining whether an invention has been disclosed in a sufficiently clear way in a patent application or patent. That is because an invention should be disclosed so clearly that the person skilled in the art can reproduce the invention based on its disclosure, again without making any significant own conclusions.

Further, the level of knowledge of the person skilled in the art is important when determining whether two different technical solutions can be considered equivalent.

See also:

The problem-solution approach in determining inventive step

Inventive step is one of the most important criteria of a patentable invention. At the same time it is one of the most difficult criteria to define.

In order to be inventive, an invention should not be obvious to a person skilled in the art. The term “obvious” is, in turn, typically defined by evaluating whether a particular development is to be seen as a part of the expected progress of the relevant technology, or whether it could be considered unexpected.

A few different methods have been developed to help with the evaluation of inventive step. The problem-solution approach is a commonly used method particularly in Europe.

Although the original goals of said approach included that it would make it possible to evaluate inventive step in an objective manner, by avoiding hindsight, particularly the latter part of this goal has been challenging, also using this method. A successful evaluation of inventive step does require the evaluation of the claim features as if these features would not be known.

However, the problem-solution approach is still highly useful.

Based on the Guidelines for Examination, originally drawn up for the Examiners of the European patent office, the problem-solution approach contains three main steps:

The closest prior art is the publication that would have been the most promising starting point for any such development that would have resulted in the invention to be evaluated.

The most important issue to consider, when selecting the closest prior art, is that the publication should belong to the same, or a very close, technical field as the invention that is evaluated.

They can both, for example, describe a fibrous product, even if they describe products having different properties. Thus, the technical field could be “fibrous products”.

Secondly, the document representing the closest prior art should be intended for the same purpose as the invention to be evaluated, for example by aiming at improving the same property.

In practice, it is common to merely carry out a comparison of the structural and functional features of the invention and the corresponding features described in the publication.

In defining the objective technical problem, the differences between the invention to be evaluated and the document selected in the previous step to represent the closest prior art are first determined, as well as the effects or advantages achieved using these differences.

Typically, the definition is based on asking how a specific effect or advantage, that is not achieved using the closest prior art, could be achieved for a specific method or product in a specific technical field.

The objective technical problem can be said to be a problem that is solved by the invention to be evaluated, but not solved by the closest prior art. It may for example be related to an improvement of the solution of the closest prior art, or it may relate to an alternative manner of achieving a certain desired effect, i.e. a manner that is different from the one of the closest prior art.

This is a difficult step of the method, where also a patent professional may fumble. It is very easy to take a shortcut in defining the objective technical problem, and merely make a general comparison of the improvements made in the new invention to various known alternatives, or combinations of such known alternatives. This does, however, not comply with the guidelines for the problem-solution approach.

In defining the objective technical problem, only the document selected to represent the closest prior art should be used for said comparison. No other known alternatives should be taken into account in this step, no matter how well known they are.

In the final step of the problem-solution approach, it should be determined whether the person skilled in the art could solve the objective technical problem defined in the previous step, using one further disclosure.

In other words, would the person skilled in the art, based on a second disclosure, have made the decision to carry out the needed changes or improvements to the disclosure of the closest prior art in order to achieve the invention to be evaluated.

Therefore, other prior art, in addition to the closest prior art, can finally be considered in this step of the problem-solution approach. More precisely, the disclosure of the closest prior art can now be combined with the teachings of one other publication.

For example, a method to be evaluated might be considered obvious (not inventive) if it can be achieved by adding one method step from a second publication to the method of the closest prior art.

Such a combination of teachings from two prior art documents is acceptable if it can be demonstrated that the person skilled in the art would have had a reason to read the second disclosure. This second document being from a similar technical field as the closest prior art is, however, a perfectly acceptable reason.

The combination of teachings should also be simple to perform, and not require any unreasonable modifications of the steps already disclosed in the closest prior art. Preferably, the closest prior art should also contain some incentive that guides the person skilled in the art to find improvements in the type of technology that is described in the other document.

If such an acceptable combination of documents is found, the invention to be evaluated is considered to be obvious.

In the past, it has been possible, for example when responding to an Office Action, or in opposition cases, to argue in favor of, or against, inventive step by briefly referring to the differences between the invention and the closest prior art, and to the advantages achieved using these differences, or the lack thereof.

However, during the past years, patent offices have adopted a more strict approach, where the complete problem-solution approach should be presented also in simple cases.

Even if it might feel unreasonable, it may have a clear advantage in some cases. When the complete problem-solution approach has been presented once, it can easily be referred to in subsequent proceedings.

The EPO started having more oral proceedings by videoconference last spring. Since April 2020 all oral proceedings in examination have been held, and will continue to be held, by videoconference unless the applicant provides serious reasons why the proceedings should be held at the EPO premises. In the past these oral proceedings could be held by videoconference if the applicant so requested and the EPO agreed.

Oral proceedings in opposition have been held by videoconference in certain cases since May 2020 in the context of a pilot project. At the moment and until the end of the year, all parties must, however, agree to videoconference. At the beginning of 2021 and for the time being until 15.9.2021, all oral proceedings in opposition will be held by videoconference. As with examination, the parties can request the oral proceedings to be held at the EPO premises if they can present serious reasons. The EPO has the right to decide whether they accept the request or not, and this decision is not separately appealable.

Oral proceedings in front of the Boards of Appeal are also possible by videoconference, but for the time being consent of all parties is required. The Boards of Appeal, however, have suggested that agreement of the parties may not necessarily be required in the future.

The reason for the change of practice at the EPO is presumably mainly the fact that only a limited number of parties have agreed to oral proceedings held by videoconference. The continuing situation with the virus leads to significant delays in proceedings as well as to a backlog of oral proceedings.

The technical means used by the EPO are Skype for Business and Zoom, the latter being used when there are several parties and/or interpretation is required. The parties, even different persons of a party, may participate in the oral proceedings from different locations.

A particular advantage of the new practices compared to earlier is that in case technical problems prevent proper conduct of the proceedings, and the problems cannot be solved during the proceedings, the oral proceedings are rescheduled.

As mentioned above, the parties can refer to serious reasons and request oral proceedings to be held at the EPO. The EPO has already communicated that distrust of the security of videoconferencing or missing technical means, for example, are not considered to be serious reasons. In practice, acceptable serious reasons could most probably be, for example, a need to hear a witness or to show a concrete model of the invention.

One advantage of videoconference is naturally the savings in travelling time and costs. The parties do also not need to stress about delayed or cancelled flights.

In some cases, the day preceding the oral proceedings is the day when the client and the attorney can, while preparing, concentrate solely on the proceedings at hand. This preparation together may thus be missed out, especially at these times of “let’s avoid physical meetings”, and when the client and the attorney are not from the same or close locations.

Having myself participated in one opposition oral proceedings by videoconference, I would say that in addition to not having the usual stress of travelling, I especially appreciated being able to take my time settling down in front of the computer, organising my papers and other equipment. I think that a good camera and a big screen ensure that one does not miss even the slightest hint of non-verbal communication from the opposition division.

Starting from the beginning of 2021 one does not usually have a choice in practice, at least until September. It remains to be seen whether oral proceedings mainly by videoconference will continue once the situation with the virus calms down.